SPHERICAL CYCLOID

| next curve | previous curve | 2D curves | 3D curves | surfaces | fractals | polyhedra |

SPHERICAL CYCLOID

| Curve studied by Jean Bernoulli in 1732, and later by Hachette in 1811, and by Reuleaux. |

| Cartesian parametrization: Spherical curve, algebraic iff q is rational (degree = 2(numerator + denominator of q)). |

A spherical cycloid is the locus of a point on

a circle rolling without slipping on a fixed circle, the angle between

the two circles remaining constant equal to ;

here, a is the radius of the fixed circle,

that of the moving circle, and xOy the plane where lies the fixed

circle.

| When Therefore, the spherical cycloid is a roulette of the motion of a sphere over a sphere. |

|

| Therefore, except in degenerate cases, the spherical cycloid is also the locus of a point on a cone of revolution that is rolling without slipping on a cone of revolution with the same vertex: these two cones are the cones with vertex W that contain the fixed circle and the moving circle, respectively. |   |

| If q is rational, then the spherical cycloids

are composed of a number of isometric arches equal to the numerator of

q.

If q is irrational, then they are composed of an infinite number

of isometric arches.

The arches meet at cuspidal points, obtained for When In the intermediate case If we change q into q/(q + 1) and

|

|

In

this animation, the circles passing by the vertices of the two cycloids

have the same radius, but not the same altitude.

In

this animation, the circles passing by the vertices of the two cycloids

have the same radius, but not the same altitude.

Special case q

= 1 (base and rolling circles with equal radii) :

Cartesian parametrization: |

|

The curve is the intersection between the sphere |

The superb models below show the generation of spherical cycloids by the rolling motion of a cone on another cone.

|

|

|

Each point of the wheels of these bikes describes a spherical epicycloid. |

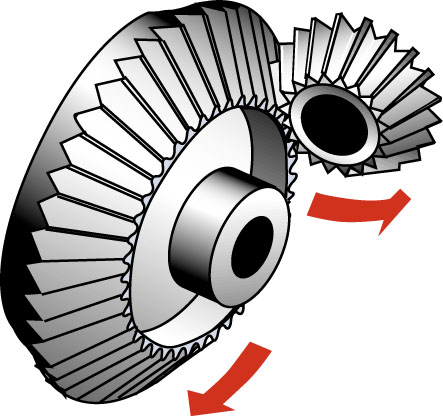

The relative movements of the conical gears describe spherical epicycloids. |

See the generalization to spherical

trochoids.

| next curve | previous curve | 2D curves | 3D curves | surfaces | fractals | polyhedra |

© Robert FERRÉOL, Alain ESCULIER 2018